Chief security officers must communicate with the Board in a risk-focused, business-aligned, and data-centric manner to inspire confidence in management.

In a business landscape that is increasingly complicated by cybersecurity threats, Boards should expect effective communication on the cybersecurity risk management program from company management. That communication should come from the individual most qualified to convey the information: the company’s chief security officer (CSO) or equivalent accountable executive.[1]

In 2023 alone, there were at least 2,800 reported cybersecurity incidents[2]. All organizations are now vulnerable to both opportunistic and targeted attacks that can cripple their business within hours. Boards and management are increasingly being held accountable, and every director I have interacted with knows of or has been involved in a cybersecurity incident featuring significant losses.

For many directors, cybersecurity and technology are moving at the speed of light. Today’s state of the art is tomorrow’s obsolete. The asymmetric state of cyber warfare (that is, that there are millions of attackers, tools and services to launch attack are in the hundreds, yet most organizations only have limited cybersecurity staff to defend against all these attackers and threats) means that it is difficult to quantify risk; and correspondingly difficult to obtain assurance of mitigation no matter the amount of money spent.

The next several sections discuss what Boards should expect from their CSO in the form of a periodically delivered cybersecurity briefing.

Industry Update and Company Implications

Every director reads newspapers, websites, and blogs, and sees stories about ransomware, large data exposures, bugs, vulnerabilities, regulatory fines and more. However, these stories rarely detail the risk implications of cyber incidents to their organization. The Board must expect that the CSO:

- Is knowledgeable about recent high-profile cyber incidents.

- Can explain cybersecurity incidents so that all directors can understand the business impact to the entity that was affected.

- Will discuss the implications (specifically, risk) from a similar incident at the company.

- Will lay out the steps taken by the company to mitigate the risk, if any.

For example, in 2022, there were headlines about ransomware strains, such as Hive and Conti, which were used to attack Costa Rica’s government services and bring them to their knees.[3] In addition to shutting down Costa Rica, there were more than 1,000 other victims of Conti ransomware. But the headlines and the technical reports were not easy for directors to ingest. The Board should expect the CSO to explain how the ransomware spread so quickly within Costa Rica and point out if/why the company was also at risk. The CSO might then explain that the risk did not manifest because of a strong, metrics-driven cybersecurity vulnerability management program. A timeline of the ransomware event, overlapping with what the company had done to mitigate the risk internally, would be appropriate. If there are tactical initiatives the company is embarking upon because of the elevated risk, the CSO should summarize them. All of this – provided proactively – is what the Board should expect.

Company Cybersecurity Posture

The company cybersecurity posture covers interrelated areas, such as:

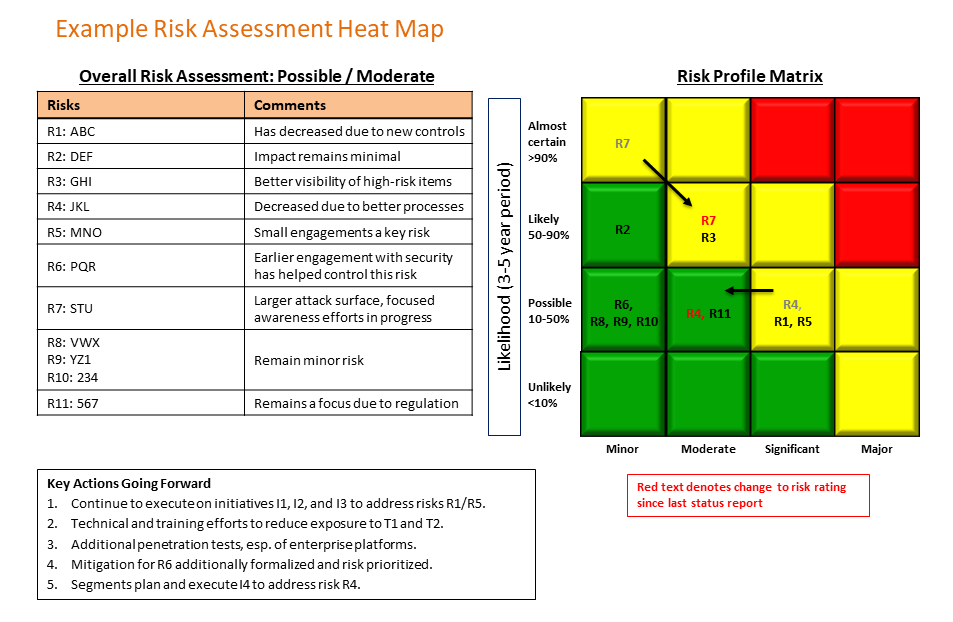

- Risk assessment. The Board should expect the CSO to demonstrate expertise of the universe of applicable cybersecurity risks and their potential impact on the company, and that the company is implementing appropriate measures to mitigate the identified risks. I prefer a standard heat map with associated explanations (see below), but there are many ways to communicate a risk assessment’s results. I use a mix of qualitative (expert opinion) and quantitative (controls, incidents, and data mapping) to generate an enterprise risk assessment. Rigorous financial analysis to quantify cyber risk has been attempted[4]but is not appropriate for all companies. An excellent resource for companies to use in their risk assessment process is the Private Directors Association position paper on Cybersecurity Governance for Boards[5] - it discusses identifying critical assets, the cost of exposure/loss of these assets, the nature and type of attacks, and the cost to protect against threats.

The Board should ask the CSO to explain his/her methodology for risk assessment. For example:

- What qualitative elements have been considered? (For example, the opinion of interested experts on the impact of a manifested risk) How has bias been accounted for?

- What quantitative factors have been considered? (For example, the number of cyber incidents by category; or the online attack surface as measured by the number of web applications deployed to the internet.) How accurate and complete is the data in this analysis?

- Key incidents and trends. In every company, there will be cybersecurity incidents of differing impact. The Board should expect a briefing on key incidents, their root causes, failures in controls, lessons learned, and projects initiated to ensure continuous improvement. Directors should receive reports on trends in incidents or control failures as well as what has been done to counter attacks or phishing attempts. Boards gain confidence when they know that, while there will be incidents, there is a measured, analytical process for managing them and ensuring that lessons learned are incorporated into the cybersecurity program. Bear in mind that Boards should be concerned if there are no reportable incidents in two consecutive reporting periods, as that may indicate deficiencies in the company’s monitoring controls.

- Key projects. This update must be consistent with the risk assessment and key incidents update. It should also be aligned with the strategic direction, discussed below. Why? Management should not initiate a project unless it is strategically planned, related to significant risk as indicated by the risk assessment or related to control failures or gaps that led to incidents. CSOs who use multiple data points across the company to create a coherent strategic journey that is immediately obvious to non-experts (like the Board) engender confidence in the cybersecurity program.

Education on a Relevant Cybersecurity Topic

Education is not a reporting topic, per se. However, the author has found from ten years of Board updates that this is a key element of the management – Board relationship. Knowledge is power – and CSO’s that educate directors gently on complex topics in a business and risk-focused manner help directors ask the right questions and fulfil their governance responsibilities in a manner that is advantageous to the company.

Directors often are, or have been, high-level executives within their companies. They are not used to being the least knowledgeable person in the room on any topic. However, as a group, they are often not cybersecurity experts. The field of cybersecurity moves so swiftly that even experts in the field can be left behind. Directors should ask simple – but searching – questions such as:

- What is the cloud, and what are the security implications? If our cloud is hacked, who bears liability?

- Why should or should we not outsource cybersecurity functions, such as monitoring?

- What is the dark web? Why is it called that? What information is on it? Are we monitoring the dark web for leakage of company information?

- Acme Inc., our largest competitor had a security incident and now they are using 3 sets of tools to do X. Should we do the same? What are the tradeoffs?

- What is ransomware? What if we just paid the hackers? How have we prepared for a ransomware attack?

Directors are understandably loath to admit to a limited knowledge of cybersecurity. The Board must expect (or request) an educational component at every briefing. This topic may be something recent in the news (such as SQL injection), it may be something that aligns with the company strategy (like cloud everywhere or digital transformation), or it may be something catastrophic to the business (perhaps ransomware). The Board is entitled to a thoughtful and gentle explanation of the topic, the implications for the company and what the cybersecurity organization is doing to address the risk.

Strategic Direction

Directors should not only want to know that immediate cybersecurity threats are being addressed efficiently, but also expect assurance that leadership is looking ahead of the curve. While some threats are universal and long-lived (such as social engineering), others come and go quickly. The Board should expect a measured, strategic, forward-looking direction of progress.

For example, the CSO might extrapolate risk assessment results to devise a three-year strategic plan to implement multifactor authentication for all employees. In a smaller company, these plans may be compressed into just months. Indeed, one of the core challenges for a CSO (as it is for all executives) is to balance the “right now” tactical initiatives with the “forward journey” strategic ones.

As another example, the CSO might provide a strategic direction for application security for a multi-national organization, which focuses on employee training, upgraded toolsets, and protection at scale:

- Today, year 0: Ad hoc processes for software development & application security.

- Year 1: Developer training on secure coding; penetration testing of key applications.

- Year 2: Web application firewalls for key applications; introduce code review tools.

- Year 3+: All new applications follow secure development framework; existing applications are retrofitted with automated code reviews, web application firewalls, and periodic penetration testing.

The Board should be concerned if the company’s strategic direction is inconsistent with the risk assessment, does not improve poorly performing program metrics, or does not look to improve cybersecurity incident trends.

Operational Efficacy

The Board should ensure that the CSO is not communicating operational performance indicators that are too technical, do not have a correlation to risk & business value, or are not controllable. Indicators of operational efficacy must be aligned with the risks identified in the company risk assessment. For example, a key risk might be exposure to attacks from publicly exposed websites. A key mitigation strategy would be a vulnerability management program. CSOs could demonstrate operational efficacy by measuring the number of applications scanned, the coverage across the enterprise, the number of open high-risk vulnerabilities, and the average time to remediate a high-risk vulnerability. Boards should question CSOs keenly about their choice of metrics to make sure the metrics are:

- Specific.

- Controllable.

- Actionable.

- Directly correlated to risk and business performance.

- Straightforward to measure and have little ambiguity.

- Comparable, either to reasonable industry practices or to industry benchmarks.

- Trend-capable, to show improvement or regression over time.

As another example, the three biggest risks for a company may be its external web footprint, phishing and social engineering, and third-party vendor management. Appropriate indicators of an efficient operational process may be:

- Coverage and visibility of vulnerabilities on web properties; open high-risk vulnerabilities; and the mean time to remediate a high-risk vulnerability.

- “Click” and reporting results from phishing simulations of employees; occurrence of successful or near-miss phishing attacks on email.

- Percentage of high/medium/low-risk vendors who have completed risk assessments satisfactorily; occurrence of security events at vendors and actions taken by the company.

Bonus: What a Board does not need to know

- Budgets & benchmarks – There is a trend in the industry to ask CSOs to report on total cybersecurity spend, cybersecurity spend as a percentage of IT spend, cybersecurity spend as a percentage of revenue, and cybersecurity spend per employee. Furthermore, there is an expectation that the percentages align with benchmarks such as those provided by Gartner or IANS. These are flawed analyses – since cybersecurity is a distributed and embedded function in a company, a canny CSO can meet any expected benchmark number by adding or removing areas “in scope.” In addition, CSOs should not be penalized for being efficient (e.g., if they use automation). A better conversation topic is to ask the CSO to report on total dedicated cybersecurity spend (even if across multiple departments) and justify how that is appropriate for the size and risk posture of the company. On an ongoing basis, Boards should ask for a briefing on the change in the company’s cybersecurity spend profile and how it relates to the change in the industry’s environment complexity and risk.

- Meaningless technical metrics/indicators – Many CSOs advanced in the technical ranks (firewalls, networks, applications). There is a temptation to inundate the Board with snazzy technical indicators – for example, “We blocked 21M attacks last month.” These are not valuable except to provide one-time scale indicators. The same holds true for numbers that are designed to impress – for example, “We installed 53 different patches on 73,500 machines across 107 countries.” That’s just your job, Mr. CSO – and unless these actions are the result of a security strategy being deployed or in response to a specific threat being identified and mitigated, it’s not something the Board needs to know.

Conclusion

High-performing Boards will achieve confidence in the company’s cybersecurity program by ensuring that their CSO addresses the following topic areas at least twice a year.

- Industry Update and Company Implications

- Company Cybersecurity Posture

- Education on a Relevant Cybersecurity Topic

- Strategic Direction

- Operational Efficacy – this includes topics such as making pragmatic tradeoff decisions, with consideration of commercial and regulatory interests.

If directors were to ask five questions to their CSO, the author recommends these:

1. Are we investing enough and in the right areas in cybersecurity?

2. What are our top three risks and how are we addressing them?

3. What are our crown jewels assets and how are we protecting them?

4. What are our response plans during a cyber incident? What is the Board’s involvement?

5. In the event of a catastrophic (e.g., ransomware) incident, how soon can we recover business operations, and have we tested this?

Boards that provide sufficient time for their CSO to explore these topics in some detail will build enduring relationships of trust with management, understand the real-world tradeoffs that CSOs must make, and provide valuable advice in their oversight roles to ensure appropriate risk mitigation for the company.

ABOUT AUROBINDO SUNDARAM

Aurobindo Sundaram is the Chief Information Security Officer at RELX, the parent company of Elsevier and LexisNexis. RELX has annual revenues of $10B and is a global provider of information-based analytics and decision tools for professional and business customers, enabling them to make better decisions, get better results and be more productive.

[1] Sometimes called CISO, Chief Information Security Officer. Note that in smaller organizations, this role and that of the Chief Information Officer or Chief Technology Officer are often combined.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Costa_Rican_ransomware_attack

[4] For example, using FAIR (Factor Analysis of Information Risk Management)

[5] https://pdaboards.memberclicks.net/assets/Cyber%20Security%20White%20Paper%20-%20FINAL.pdf

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely those of the authors providing them and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the Private Directors Association, its members, affiliates, or employees.